Where there’s washi,

there’s prosperity

in the early period

(1925-1960s)

The Moriki family, founding family of Moriki Paper, were for a long time washi producers making paper in Ino Town, Kochi prefecture. Moriki Paper founder Yasumi Moriki’s uncle, Rinnosuke Hisamatsu was an apprentice of Genta Yoshii, the noted local figure who reformed many washi production techniques, including the development of Tosa Tengujo paper, a very thin paper for typewriting. At that time, in the turmoil of the last days of the Tokugawa Shogunate, the local Tosa clan was struggling financially, but based on the efforts of Genta Yoshii and his apprentices, Tosa Washi developed into a major production area, triggering the rebuilding of the area’s financial affairs.

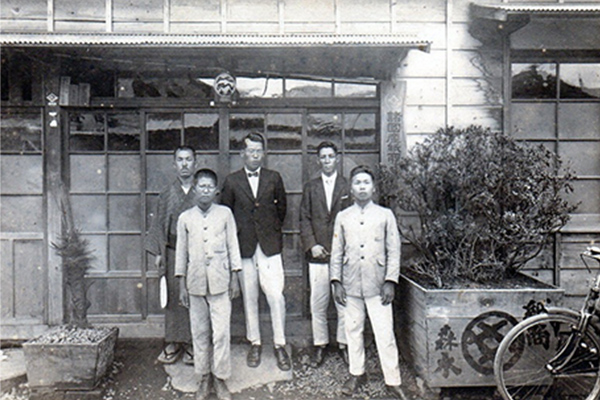

The present Moriki Paper was first established under the name Moriki Kamiten (Moriki Paper Store) in 1925 in Yokohama. The founder was Moriki Yasumi, who was born in Ino Town, Kochi prefecture in 1903, and is the great-uncle of current (3rd generation) president, Takao Moriki. The image of diligent Yasumi, who passionately loved washi, and devoted his life to the washi industry, is imprinted in the memory of all who knew him.

Yasumi was born into a family who made paper for a living, so he helped with the family business from a very young age, working late winter nights alongside the adults doing papermaking tasks such as chiri-tori, until he had a basic knowledge of the difficult work required of a paper producer. However, due to unfortunate circumstances, when he was fifteen, the family business had to be shut down, and he began working for Tosa Paper Company. He was assigned to the Yokohama office, at that time the representative trading port of Japan, negotiating with foreigners, and trading on site. Yokohama during this period was the gateway to Japan, and washi was, as one of the main industries of Japan, exported in huge quantities. In his adolescence, Yasumi was captivated by scenes of long lines of carriages carrying great quantities of washi exports, and had high hopes for the future of washi production. Yasumi, who grew up a witness to local poverty, thought, “I want to improve the fortunes of my home town through washi.” His dreams grew, such that he wanted to become independent, become a skilled trader, and purchase the local paper for as high a price as possible, bringing affluence to the local area.

Soon, with the shuttering of Tosa Paper Company’s handmade paper division, he decided to go out on his own. However, with the Second Sino-Japanese War, trade became extremely difficult, and washi exports were reduced to nothing. Immediately, WWII broke out, and in wartime the manufacture of munitions became the priority; in washi production areas they made paper balloon bombs, but there was very little need for traditional crafts, including washi. Returning from his military post in the Philippines, Yasumi was finally able to restart the washi export business. In order to remind people of the existence of long-forgotten washi, he contacted previous business connections and acquaintances, and distributed a washi sample book to many trading companies. After doing so, as if they had been just waiting for the revival of washi, orders from various countries poured in. Of course the Japanese, and foreigners too, were weary of the war, and they must have been eager for the pure warmth of washi.

Among the papers of the world, washi was (and still is) the most elegant and flexible, as well as the strongest. In many foreign countries, the introduction of Japanese production techniques was attempted, but they couldn’t make papers of the same quality, and had to give up. There was some aspect of the craft that only the Japanese were able to master.

However, because the production of paper balloon bombs and inferior quality washi had continued for such a long time during the war, the papermaking studios were not clean enough and the quality of the finished papers was poor, with the result that there was a lot of paper that couldn’t be exported. Also, because many papermakers had been deployed to the frontline during the war, inexperienced or elderly papermakers were all that remained. In this reality, Yasumi travelled around to many papermaking studios, offering guidance.

At the time, many foreign countries were demanding exclusively high grade papers; if not for the Japanese, with their exceptional techniques, those papers could not be made. Because customers in foreign countries desired top quality unbleached or pure white washi, as has been made in Japan since ancient times, Yasumi went around the country to Kochi, Ehime, Shimane, and other prefectures, visiting people in every location skilled in papermaking, asking for cooperation, and once again setting up a system for exporting washi extensively.

Even with the post-war shortages, Yasumi managed to find – and encourage papermakers to make – high quality washi just like that made in ancient times. From around this time, while avoiding unreasonable price wars by dealing with one company in each country, Moriki Kamiten (Moriki Paper Store) began to gain the trust of many trading partners around the world, and expanded the market. From that point on, traditional high-grade washi was revived in every part of Japan, and sent overseas.

The Reminiscences of Yasuo Kobayashi of Kadoide Washi

My first connection to Yasumi Moriki was when I was in my early twenties. On the occasion of the “All Japan Handmade Paper Association” meeting, Professor Yagihashi of the Agency for Cultural Affairs had taken me along, and he introduced me to Mr. Moriki. At that time it was our first meeting, but he said “by the way, I have a papermaking screen in my storehouse; I’ll send it along to you.” He sent 3 very large and excellent screens to me in Niigata. At that time, I was just a beginner, struggling to acquire tools, and I was very thankful, so I sent some yams from my garden as a way of thanks. After that, I saw him at his home and other places, and I was fortunate enough to keep in touch with him for several decades. He had a typical Meiji manner about him; he was straightforward and resolute. Among papermakers, he was regarded as a highly intellectual person, up in the clouds. Since everybody was a bit tense around him, I was nervous at first, but actually he was such a gentleman, and gradually I felt at ease with him. He had an athletic build and his fashion was unlike the common Japanese person, but I can clearly remember that his clothing was always perfect and his shoes were always gleaming.

Handing down

the spirit of family

in the growing period

(1970s - 2010s)

Beginning in the 1970s, management of Moriki Paper was handed down from Yasumi to the next two generations: father-and-son Shinji and then Takao. Directly taking over the business from founder Yasumi was Yasumi’s nephew, current president Takao’s father, Shinji. From the early days of the company, information exchange with overseas customers was very active, but as for trade, persistent problems with exporting and exchange meant that much of the trade was done through domestic companies. Proceeding from these conditions one step at a time, Shinji began direct business with America in 1979, and West Germany in 1983, and exports to the West began to gain momentum.

Business changed from domestic trade and brokered transactions to direct communication with various foreign countries. While increasing cooperation with washi cooperatives of production areas such as Echizen and Tosa, and holding more papermaking demonstrations and exhibitions in foreign countries, Moriki Paper became more active showing visitors from foreign countries to Japanese papermaking areas. Current president Takao, from around his teens, accompanied his father as he actively expanded business in Western countries such as America, Canada, Germany, and Britain, observing and directly experiencing overseas trade.

Several decades after Yasumi, in the 1990s, washi exports were faced with a new problem. There were reports circulating in the West that among washi with the same name there were a lot of poor quality imitation products. With the increase in washi products, products that didn’t maintain genuine washi’s high quality standards were released onto the market as Japanese products. Among these were copies of Japanese unryushi and rakusuishi papers, whose production had begun in southeast Asia, especially Thailand. Also, there was a period in the late 1990s when long-term partners in the West were bought by large companies, or their owners changed, and for many reasons the overseas washi market changed greatly. Faced with these circumstances, Takao quit the company he was working for and joined Moriki Paper in 2000. With the mission to once again supply the high quality washi that customers wanted, Takao and his father – whose knowledge of Japan’s washi was extensive – actively visited various foreign countries, and more than ever engaged in information exchange with overseas partners. Soon, they were able to further increase trading partners to include Australia, Singapore, Malaysia, and others.

Takao took over the business from Shinji and became company president in 2008. In June of the same year the World Washi Summit was held in Toronto, Canada, a huge event planned by Moriki Paper’s North American partner The Japanese Paper Place, in cooperation with Moriki Paper. There were papermaking demonstrations by the three young papermaking craftsmen who were invited from Japan, and for more than one month in more than 30 galleries in the city, artworks that used washi were exhibited, and various lectures and workshops were held at art museums, museums, libraries, and art universities in and around the city. During the Summit a bazaar to sell paper, and a washi fashion show were held. It was an important opportunity for exchange between people who regularly make use of washi – artists, companies, conservators, and craft artists – and the papermakers.

Since the foundation of the company the core of trade has been with the West, but lately the market is gradually expanding to Asian and Middle Eastern countries, such as Vietnam, India, Indonesia, Turkey, and the UAE. At the same time, Moriki Paper regularly participates in foreign partners’ exhibitions and in various meetings, such as The Japan Society for the Conservation of Cultural Property. In order to hear directly from end-users in places such as printmaking, bookbinding, and conservation studios, the frequency of visits to these studios is also increasing.

In 2014, the traditional handmade washi making methods for Sekishu Banshi, Hon-Minogami, and Hosakawashi were registered as UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage items, and global attention has once again become focused on the value of washi. As one of the only companies in Japan focused for many years on washi exports, Moriki Paper is increasingly asked for opinions or advice on various occasions. As a result, Moriki Paper is more than ever actively working to broaden the understanding of washi’s potential and importance at washi-related events both in and outside of Japan.

In the devastation immediately after the war, washi gave people hope. Now, even 70 years after the war, Moriki Paper strives to deliver to the world the same high quality washi that Yasumi did. It has been 90 years since the foundation of the company, and “the Moriki mindset” of conveying the true value of washi has been handed down over three generations, and will continue into the future.

Text: Murashiki Inc.